This month I had the amazing experience of attending SocratesUK. On the first main day, a session was proposed by Ian Johnson titled Functional Calesthenics. Ian’s plan was to try and get the group to come up with an equivalent to Object Calisthenics for functional programmers. This session turned out to be amazingly popular, and spawned a theme which continued through the rest of the event.

At the end of the session a list of proposed calisthenics was produced. During the rest of the event, various groups set about trying to apply them in different languages - mostly in the context of the Social Network Kata). I decided that I’d have a go at it in Clojure and see how they applied.

Before talking about my experience, I’d like to share a few thoughts…

Object Calisthenics

The Object Calisthenics are a fantastic set of rules. The 2 things which make them great for me are:

- By using them in your day to day code, they will help you write great code. Sure, applying them rigorously over every single line of code might not be much help outside of an exercise. However, you can (and should) successfully apply them to about 90% of your code.

- They work with every OO language. Some rules may apply more or less in some languages than others. But on the whole, they mostly apply.

The other point I’d like to make, is about the times when Object Calisthenics do not apply well. In your domain model, you should be able to apply Object Calisthenics to nearly 100% of your code. The places when bending the rules seems to be more objective (in my experience), are in the pieces around the domain model - typical UI and persistence layers.

The Discussion at Socrates UK

This was a very popular session at Socrates. I think there was probably around 20-30 of us present. This caused a suggestion for us to use divide and merge, so we broke off into smaller groups. The session only lasted for 1hr and most of the time was spend as the groups discussed theoretical ideas of what rules could be useful.

At the end, we only really had about 5 minutes to merge the ideas. This didn’t involve a huge amount of discussion, and ultimately amounted in gathering the unique ideas and sticking them on the list. The final list looked like this:

- Side effects can only occur at the top level

- No mutable state

- Expressions not statements

- Functions should have 1 argument

- No explicit recursion

- Maximum type-level abstraction

- Always use infinite sequences

- No “if”

- Name everything

- Use intermediates

- Don’t abbreviate

More details can be found on Ian’s blog.

Really, I felt this session was too short and could have done with far more in depth discussion. Also, since we had divided, I missed out on some of the reasoning used to reach some of the rules (specifically Functions should have 1 argument).

My Experiment

Since everyone was playing with the Social Network Kata, I figured I’d do the same. I’d not done this kata before but it looked straight forward enough. I started toying with some ideas at Socrates (both with Johan Martinsson and Ross Huggett) but due to time limitations and tiredness, the attempts didn’t go anywhere. Since then I’ve been toying with it and trying different approaches. The code I’ve ended up with is on GitHub. This code doesn’t obey all the Functional Calisthenics rules set out above, but in places where it doesn’t I made specific reasons why - details below:

The Rules Which Didn’t Apply

First up, some of these rules just never came up in this kata. This doesn’t mean they are no good, it just means I’ve not had to apply them here.

The first 3 of these were:

- Expressions not statements

- No explicit recursion

- No “if”

As far as the actual data transformation and algorithms which appear in this kata go, it’s actually pretty boring. Since I’m already pretty comfortable at thinking with a functional mindset, I found that the first 3 rules didn’t come up. In the places where someone who is very new to functional programming might have tried looping/recursing with conditions, I’d already decided on using filter.

While I’ve not played with it enough, I think these first 3 rule are decent and valid rules.

Maximum type-level abstraction

This rule also didn’t come up in my experimenting.

When working a strictly typed functional language like Haskell, this rule is exceptionally important. However, with Clojure being a dynamically typed langauge I didn’t really consider it. I think a more applicable rule for Clojure (or any dynamically typed languages) might be “Make you functions as generic as possible”

I think that both the original rule and my somewhat more vague one, are vital to writing good functional code. The problem is that there is no way to know that you have complied to the rule. It’s very easy to look at some OO code written with Object Calisthenics and see whether any given rule has been broken. With this one, you may not be able to see/conceptualise the more generic/generalised solution.

This to me seems similar to someone asking you to write a sort program, then you produce a bubble sort algorithm. Someone could come an tell you that you should have produced a quick sort algorithm instead. Without extra knowledge or deeper thinking, there’s no way to say one is right and one is wrong - we can just say that one is better.

The obvious ones

- Name everything

- Don’t abbreviate

- Use intermediates

These are good rules, and I think we can all agree on them. Maybe the last one is a bit less obvious though?

In Clojure, this is saying to prefer this:

(defn make [author message]

(let [mention-matches (re-seq #"@([A-Za-z0-9]*)" message)

mentions (map second mention-matches)

link-matches (re-seq #"(http://[^\s]*)" message)

links (map second link-matches)]

(Message. author message (set mentions) (set links))))over

(defn make [author message]

(Message. author

message

(set (map second (re-seq #"@([A-Za-z0-9]*)" message)))

(set (map second (re-seq #"(http://[^\s]*)" message)))))Those may not have been the best examples, but hopefully the first one is some what clearer. However, the second one looks more concise.

I think, because pure functions compose so well, it’s easy for more experienced functional programmers to string long sequences of functions together. This may even look more elegant to them. However, in this day and age we know to favour the reader, and to try an convey as much information through our code as possible. For this reason, this rule gets the thumbs up from me.

Clojure’s short lambda syntax

There are 2 syntaxes for creating anonymous functions in Clojure:

(fn [value] (* value value))And:

#(* % %)I think the Name Everything rule should enforce the use of the first method. However, in my code, I’ve used the second method a lot - I just like it for small single argument functions.

Side effects and mutable state

- Side effects can only occur at the top level

- No mutable state

I like these rules. However, I think the second one is unnecessary and implicitly covered by the first.

I do find is poses a couple of interesting questions though:

What exactly is the top level?

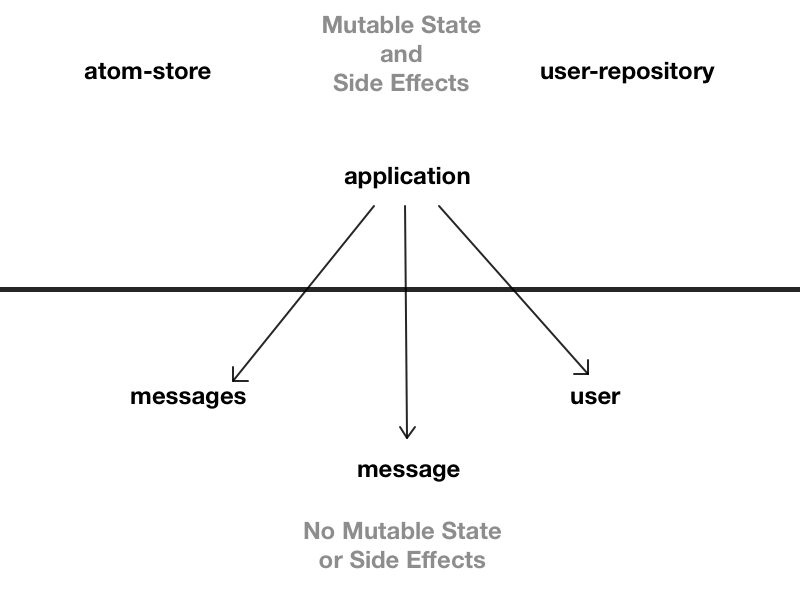

For your software to do anything useful, it’s going to have to deal with and/or produce side effects. What this rule means to me, is that you should have a functionally pure domain model and the code which deals with side effects should be outside of (and not depended on by) this model.

This to me is the same as building dependency free OO domain model. Then calling it from outside and plugging in the implementation details via abstractions - as we see when using Hexagonal Architectures.

In functional programming I think we can consider that: inside the hexagon we should have only pure functions. This side effecting code only exists outside. The skill is then to push all the important logic inside the hexagon.

In my Clojure experiment I decide whether each name space was allowed to make cause side effects or not. It ended up looking like this:

What is considered causing a side effect?

We can all agree that calls to functions which cause any sort of input or

output in are side effecting ((println) and (read-line) for example). And,

I’ve also state the changing mutable stage is a side effect also.

Now, consider a function:

(defn add-and-output [a b]

(println (+ a b)))

(add-and-output 4 5)add-and-output is obviously causing a side effect. But how about

add-and-action below:

(defn add-and-action [action a b]

(action (+ a b)))

(defn print-action [value]

(println value))

(add-and-action print-action 4 5)This time, we’re passing in an action which is an abstraction to a side

effecting function. Now, action could return a value and this would be a valid,

pure function. But, if this is written with the intention of action being a

side effect causing function (and the return value is not important), then I’m

going to consider add-and-action to be a side effect causing function.

Maybe we could add a new rule here:

- Always use the return value

Or maybe that’s implied by Side effects can only occur at the top level?

Thinking about side-effects help me a lot. A one point I had some code which looked like this:

(defn- get-public-messages [message-store]

(let [fetch-all (:fetch-all message-store)

messages (fetch-all)]

(filter message/public? messages)))

(defn my-feed [user-repository message-store active-user-name]

(let [fetch-user-by-name (:fetch-by-name user-repository)

active-user (fetch-user-by-name active-user-name)

follows (:follows active-user)]

(filter #(follows (:author %)) (get-public-messages message-store))))I thought I was being clever but hiding the reading of the message store behind an abstraction and pushing the reading down deep into the nested function calls. This was the point when I realised that essentially everything was relying on the side effects. I then broke it down into a collection of pure functions which each did one small transformation on the message stream. This resulted in some much more pleasant code:

(defn from-followee? [followees message]

(contains? followees (:author message)))

(defn public-only [messages]

(filter public? messages))

(defn from-followees [messages followees]

(filter (partial from-followee? followees) messages))

(defn- my-feed [user-repository message-store active-user-name]

(let [fetch-user-by-name (:fetch-by-name user-repository)

active-user (fetch-user-by-name active-user-name)

follows (:follows active-user)

fetch-messages (:fetch-all message)]

(-> (fetch-messages)

public-only

(from-followees follows))))As these neat little pure functions started to appear, then I saw an obvious

use for Clojure’s threading macro (->). This made me consider the ordering

of the parameters to the functions so I could make the best use of the macro.

Always use infinite sequences

This kata is a really good consideration for this. My implementation was to have all the messages stored in a big message store as a single stream. When you read your feed, you only want to see the latest x messages. You would never want to load all of history if this (totally not Twitter) social network ever took off!

Again, this kind of fell into place naturally by only performing actions which

are lazily evaluated (primarily filter in this case) on the message stream.

This means it’s up to the consumer of the application to decide how many

messages to take from any given stream.

While it didn’t take much thought in this kata, I definitely found it helpful to bare this in mind while working.

Functions should have 1 argument

I’ve come to the conclusion that I don’t think this is right for Clojure.

Take this example from my code:

(defn- timeline-for-user [fetch-messages user-name]

(-> (fetch-messages)

messages/public-only

(messages/authored-by user-name)))(defn public-only [messages]

(filter public? messages))

(defn authored-by [messages author-name]

(filter (partial message/authored-by? author-name) messages)) (defn authored-by? [author-name message]

(= (:author message) author-name))I tried re-writing this like so:

; This is outside the "domain model" so I'm allowing the parameters

(defn- timeline-for-user [fetch-messages user-name]

(let [authored-by (messages/authored-by username)]

(-> (fetch-messages)

messages/public-only

messages/authored-by)))(defn public-only [messages]

(filter public? messages))

(defn authored-by [messages author-name]

(partial filter (message/authored-by author-name) messages)) (defn authored-by [author-name]

(fn [message] (= (:author message) author-name)))I studied this for a while and decided that I had gained nothing from it. I can

achieve the same functionality using partial and I feel the first is a little

clearer. Trying to stick to this rule in all your code in Clojure will

ultimately create: more code, less understandable code, and more parentheses

(not a good thing).

That said, by always trying to reduce the number of parameters, you definitely find more generic and composeable functions. With this in mind, I think the limit should be set at 2 (maybe 3 but I think 2 should be OK).

Conclusion

At the end of this exercise I feel my efforts were time well spent - I learnt a lot. I’ve gained a deeper appreciation of some of the rules from Socrates which I took for granted. Others rules have really driven me to think about things I never would have before. And, a few I think really need to be modified or removed (at least in the Clojure context).

My rule list at the end of this exercise is:

- Expressions not statements

- No explicit recursion

- No “if”

- Name everything

- Don’t abbreviate

- Use intermediates

- Side effects can only occur outside of the model

- Always use the return value

- Always assume infinite sequences

- Functions should have no more than 2 arguments

I’m not yet convince that these are as good a Object Calisthenics, but I think the are definitely a decent set of guidelines to play with.

I’m hoping others are playing with this too, and I look forward to more discussion on the subject.