I’ve seen many people do the Fizz Buzz TDD coding kata for the first time. For this kata, you typically use the red-green-refactor cycle, while working through a sequence of input numbers to test. One thing I have observed is that often the way the problem is described to the developer affects the sequence they choose to solve the problem.

In this article, I consider some common sequences I have seen. I then offer some thoughts about choosing the best path to take when solving a problem using TDD.

There are two primary ways that I have seen the Fizz Buzz problem described to developers; these are:

1. Sequentially

Create a program which returns a list of numbers from 1 to 100, where numbers divisible by 3 are replaced by Fizz, numbers divisible by 5 are replaced by Buzz, and numbers divisible by 3 and 5 are replaced by FizzBuzz.

When the problem is described in this way, I’ve seen developers typically choose one of two sequences:

a. Counting up

This sequence considers the problem as a whole. It’s not focusing on the individual requirements, but rather the rules for each input. We start with 1 (because that’s the first number mentioned in the description) and then go up through the natural numbers — each time finding the next number that will create a failing test.

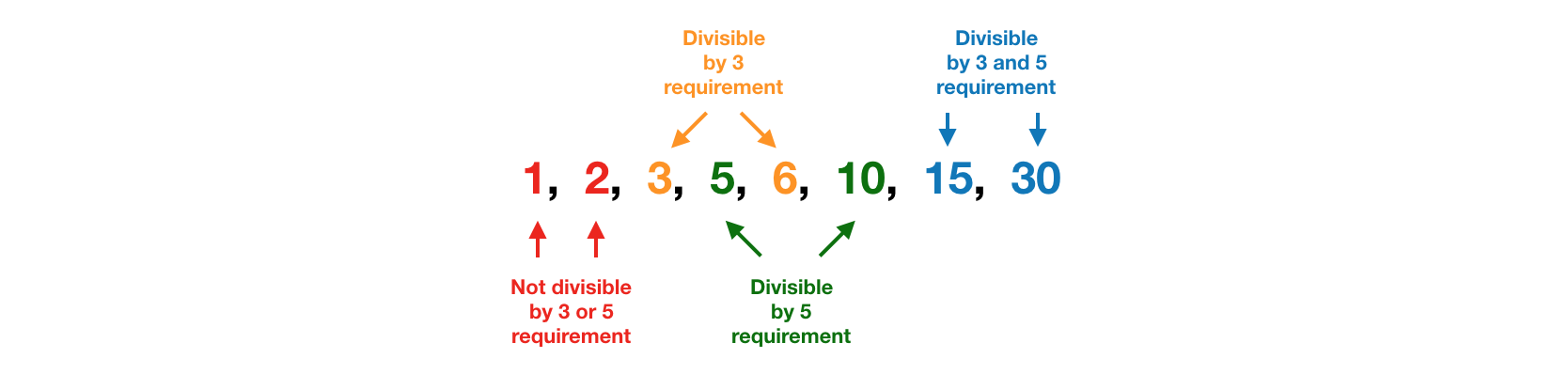

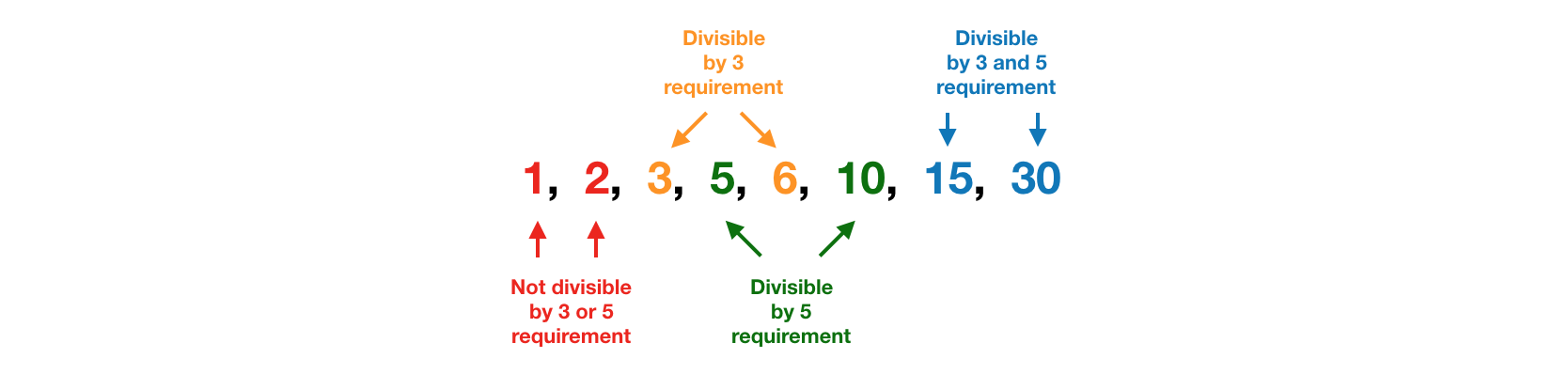

b. Addressing requirements

This sequence is similar to the one above, except that each requirement is considered in order. Starting with the non-fizz/buzz numbers, then the fizzes, then buzzes and finally, the fizzbuzzes.

2. Describing the Function

Create a function which takes a number and returns Fizz if the number is divisible by 3, Buzz if the number is divisible for 5, and FizzBuzz if the number is divisible by 3 and 5. For all other cases, return the number.

In this case, the developer very often tries to solve the “is divisible by 3” case first. Next they try to solve it for divisible by 5 case, followed by the 3 and 5 case — and finally the non-fizz/buzz case.

This approach doesn’t tend to flow as well as the sequential ones because it causes some problems in the TDD cycle. The first iteration usually ends up something like this (which is fine):

# Test

it "returns Fizz for 3" do

expect(fizzbuzz(3)).to eq "Fizz"

end

# Implementation

def fizzbuzz(number)

"Fizz"

end

However, at this point, there’s a challenge — which test to write next? Typically the person makes one of two choices — resulting in one of three outcomes:

- They choose 5 and jump straight into using

number % 3 == 0— never writing the test for 6; which should triangulate to the divisible by behaviour. - They choose 6, write the test, but never see it fail (sometimes making a copy and paste error in the process).

- They choose 5 (using

number == 3) and then do 6 next (evolving the code tonumber % 3 == 0)

Of these three options, I think number 3 is the best from a strict TDD cycle point of view. However, it does mean that we interleave the implementation of the requirements.

Which Sequence is Best

While the answer to the question is debatable, I’m going to suggest that the best approach is the second sequential one — the one which completes each requirement before moving on to the next one (1, 2, 3, 6, 5, 10, 15, 30). The reasons for this are:

- The choice of the input number for each step is methodical

- It clearly works with Red-Green-Refactor cycle without having to make awkward steps

- It completes each requirement before moving on to the next one

Error Cases and Edge Cases

One recommended technique when doing TDD is to try not to solve the happy path straight away. The idea is that you try and cover off the error and edge cases before tackling the main problem. By doing this we set up the environment that the solution will exist in first, we explore the full scope of the implementation, and we consider error cases up front rather than forgetting about them later — this approach ultimately produces more resilient code and test suites.

For a Fizz Buzz function, these considerations might include questions like “What should the return value be for zero?” and “What should happen if we pass in null?”.

One recommended technique when doing TDD is to try not to solve the happy path straight away.

We’ve seen that the order the rules are described in, often dictates the way someone will tackle a problem — they dive straight in and try and solve the first requirement they are given. We now also know that it’s advisable to consider error cases and edge cases and that often doing this earlier is better. These cases are not described in either of the descriptions above, so it suggests that we should take some time to consider the whole problem before choosing which test to write first.

Conclusion

We like to be agile and avoid Big Design Up-Front. However, if we implement the first requirement before taking some time to consider the whole problem, then with might not have enough information to choose the best route to take.

To determine the best approach to take when solving a problem, we should consider the information we are given together, and then break it down into smaller pieces.

Developer experience also plays a big part in knowing which order to write the tests. TDD coding katas are one great way to gain experience. By practising and studying different katas you can learn the best paths to take in different situations. Both the Roman Numerals kata and the Prime Factors kata also help build up familiarity with working through sequences of numbers.