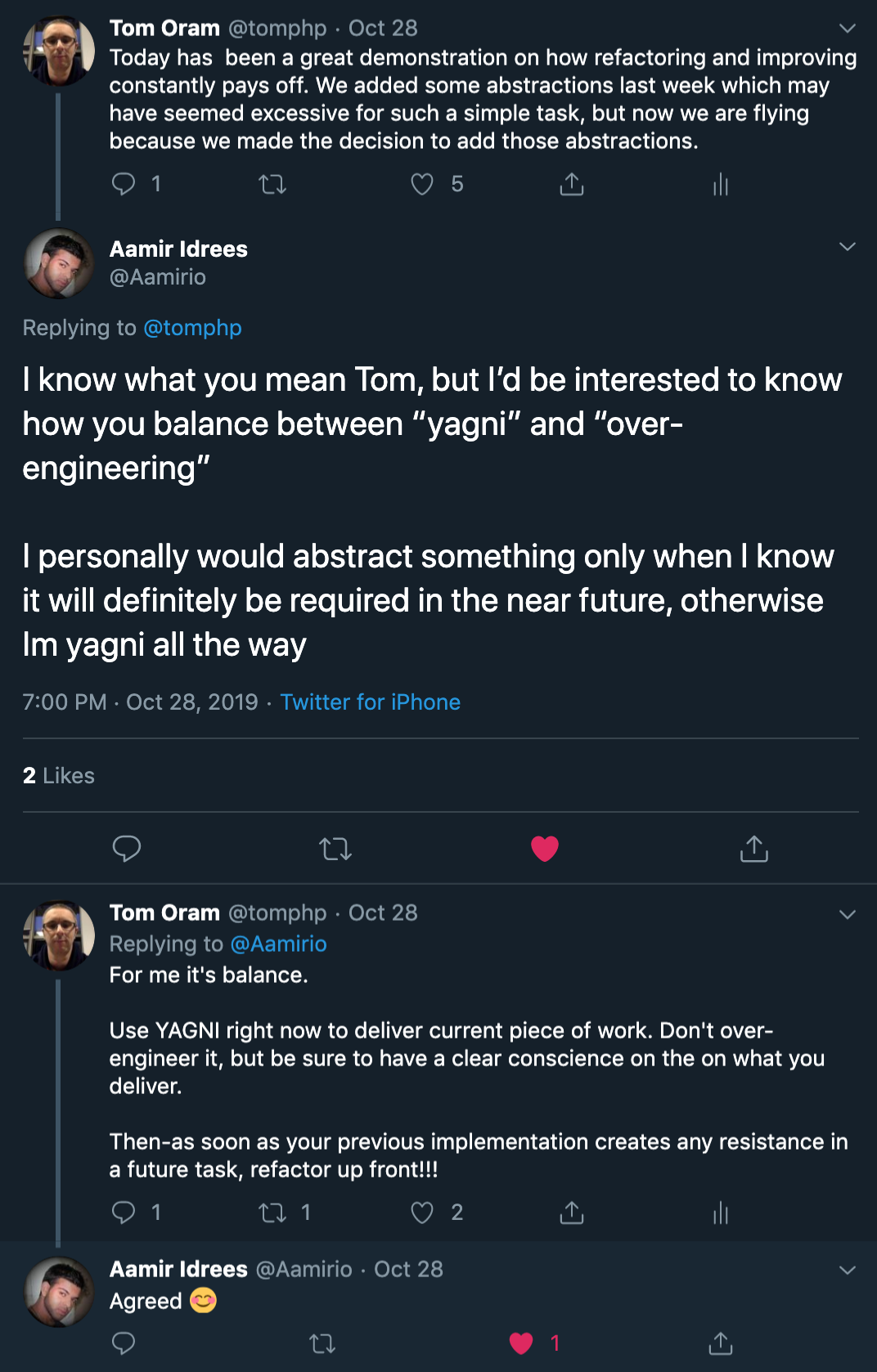

A few days ago, I posted a simple tweet about how investing in design pays back very quickly. This led to a short conversation with Aamir Idrees, about how much engineering is enough, before it starts to become over-engineering.

In my response, I said a phrase which I don’t think I’ve used before: “be sure to have a clear conscience on what you deliver”. Thinking back on it, I realise that this is my perfect way to summarise how I decide if a piece of work is complete. Here, I’d like to explain what I mean in more detail.

Having a Clear Conscience

clear conscience noun

a knowledge or belief that one has done nothing bad or wrong1

To commit code with a clear conscience, you must believe that you have not done anything bad or wrong while creating it. To quantify whether this is true, we must first understand who might judge our work as being bad or wrong. I’m going to generalise these people into three groups:

- People who benefit from the running software

- The people investing in your work

- Other developers

I now want to look at our obligations to each of these groups:

The People Who Benefit From the Running Application

I’ve intentionally made the description of this group a bit vague. It could refer to the end-users of the software, they obviously benefit from using the software (otherwise why would they use it?). However, there many other people in this category. For example:

- It could also be people downstream from the end-users (e.g. as a customer of a telephone network, I benefit from the CRM that their support staff are using when I call up to query about my account).

- It could be the people who are paying you to develop the software. The software may be the only reason they have a business.

- It could even be you and the other developers, your job may be based on the success of the software.

Regardless of who benefits from the running software, your obligation to them is to build software which performs at a satisfactory level and does not cause any harm (e.g. loss of money, physical or emotional harm, loss of productivity, etc.).

This gives us the first question to ask yourself when delivering a feature:

Could this feature have any impact on the software which might cause distress to the people who benefit from it?

Some things to consider when answering this question are:

- Are you confident that the users will be able to use it?

- Are you confident that the changes haven’t broken the system elsewhere?

- Do you have SLAs,2 SLOs3 and SLIs4 that you meet and track?

The People Investing in Your Work

Hopefully, you are being paid to write code. Hopefully, you are being paid well to write code. If this is the case, then the people paying you are paying for a reason - they want a return on their investment. The tricky part here is that not only should you deliver working features on time, but you also need to deliver them in a way which doesn’t hinder further development later on.

The question here is one you should be asking daily:

Am I doing a professional job while keeping a clear focus on what I’m trying to deliver?

The key factors to enabled you to consistently answer yes to this question, are:

- Reviewing performance retrospectively, and applying learnings from these experiences.

- Clearly communicating progress and challenges to manage expectations.

- Architecting software with a view to the future; enabling accurate understanding for future tasks.

Other developers

As part of a team, everyone should help each other succeed. By creating good quality as sustainable code, can help your team achieve their goals. Confusion or misleading code can cause other developers to loose hours trying to understand it. Tangled or tightly coupled code can be very hard to extend. Missing tests make it hard to be confident that your changes work. To have a clear conscience, we should deliver code that other team members will enjoy working with.

The question we should ask ourselves here is:

Is my code going to make the work on future features harder?

This time, I’m going to go a bit deeper into each of the factors which contribute to delivering high-quality code.

Testing

Tests enable other developers (or our future selves) to change and extend the system with confidence. Having a good quality test suite helps us avoid wasting unnecessary time checking that we haven’t inadvertently broken something.

To have a clear conscience, you should ask yourself “If something is changed that would alter the behaviour of the system, will a test fail?”

There are cases when it’s acceptable to have some code which is not tested. An example might be where the gain of testing the integration with an external system does not outweigh the effort. In such a case, we can still ask how we will know when it fails (monitoring may be) and have we sufficiently handled failure. But we should also make an effort to isolate such code so that it’s easy to identify should a failure occur.

Regardless of the specifics of testing, a clear conscience comes from knowing you have protected the code from inadvertent damage, and enabled developers to continue to develop the system.

Formatting

Having a consistent formatting style in a project reduces the cognitive load for the people reading it. When the layout is consistent, our eyes instinctively follow the code, and we don’t have to hunt so hard for the logic we are looking for.

Ask yourself “Have I laid out my code in a way which is consistent to the project?”

The important thing is that the team chooses a coding style and everyone follows it. Better yet, use a linter to check/fix your code for you. It’s important that you code to the project’s coding style, not your own. Having a clear conscience is not about you thinking it’s perfect, rather, it’s about ensuring that it doesn’t frustrate your colleagues.

Naming

The name of the variables, methods, classes, etc. is one of the best ways that we can ensure other developers can understand what the intent of the code is. Unfortunately, choosing the right name can be one of the hardest decisions a developer has to make.

Ask yourself “Have I named anything in a way which will cause confusion?”

If you can’t think of the perfect name then it’s not a problem (we have powerful refactoring tools at our fingertips which makes renaming things simple). It is a problem though if our names cause confusion or misunderstanding.

Well Architected

How we structure our programs has a huge impact on how future work is done. On

one hand, we might be able to make something work as intended with a thousand

lines of ifs, fors and gotos. On the other hand, we have a huge library

of Design Patterns, SOLIDs, YAGNIs, Laws of Demeter, Object Calisthenics, the

list goes on - and we know we should be using them all, but sometimes it seems

like too much. So what’s the right amount?

The question is simple “Will other developers curse my name when working with my code?”

We’ve all thought “What was X thinking when they wrote this code!?”. We’ve all been X. And worse still, we’ve all thought that about code where X was ourselves.

By considering if there’s anything in our code which might cause someone to ask this question, and fixing it before we deliver it, we can improve others lives and have a clear conscience.

Interestingly, the culture of the team can make a big difference to this question. If you’re working in a team of people who have a strong crafting culture, then a YAGNI approach can be the perfect way to deliver something. If you know that when someone picks up the code for the next feature, they will start to factor it into a shape which fits the evolving architecture, then this is probably the most efficient way to work. On the other hand, if the culture in the team doesn’t work this way, then you probably need to engineer the solution a bit more to ensure it guides other team members. However, in the latter case, I think efforts should be investing in improving the culture (and possibly skill level in the team).

Finally, we should make efforts to conform to the architecture of the project; it’s never fun trying to navigate some code which solved a problem in three different ways at the same time. At the same time, we shouldn’t be afraid to change the original architecture if we collectively agree it is a hindrance.

Failure Cases

Things fail, that’s a fact. If that failure causes distress to the end-users, then that’s a problem. If reported failures from end-users cannot be easily tracked down and diagnosed, then everyone suffers.

The obvious question here is “Have I handled all failure cases sufficiently?”

This can involve many things, such as handling nulls, catching exceptions, raising exceptions, displaying meaningful error messages, etc.

Other Factors

There are also many other things which might be important to consider, depending on your specific circumstances:

- Security: “Is my code secure?”, “Can any personal details be leaked?”, “Are the dependencies up to date?”, etc.

- Logging: “Have I logged useful messages?”, “Have I logged at the right error level?”, “Am I logging any unnecessary noise?”, etc.

- Accessibility: Does the design of the feature exclude anyone from using it?

There are many more, but I’ll leave it up to you to decide what is appropriate for each situation.

Summary

To have a clear conscience you must deliver software which does not knowingly do bad or wrong things in the eyes of any of these groups of people. It is not possible to do this without considering all groups. If you over-engineer the perfect solution, then the developers might be very happy, but features might be very expensive to develop. Conversely, if you rush features out the door as quickly as possible, then developers are likely to get unhappy with working conditions, and end-users are likely to get unhappy with broken features.

With this in mind, the only way we can keep them all happy is by managing expectations; bending over backwards to make one person happy is likely to have negative effects on the other people.

It’s also worth noting that these choices are context-specific; many factors can determine what the minimum viable implementation looks like. Some of these include:

- Number of users using the system

- The scale of the system, teams or organisation

- Do the developers have the right tools (e.g. refactoring tools)

I hope this article has provided some guidance towards keeping your conscience clear, while keeping productivity high.

Featured Image by Okan Caliskan from Pixabay